Parents must use a private biobank, which charges between £550 and £3,000 for freezing a baby’s umbilical cord blood. On top of this, parents must pay an annual storage fee of over £100 to keep samples frozen.

Private biobanks market their umbilical cord blood banking services to expectant parents as an investment in protecting their child’s future health alongside claims that stem-cell based therapies have been used successfully to treat a wide range of potentially life-threatening diseases, from cerebral palsy to leukemia.

But experts in regenerative medicine say many of these companies’ marketing claims are misleading.

For example, Cells4Life, which describes itself as the UK’s largest provider of cord blood banking services, claims that “umbilical cord blood is routinely used in treatments for over 80 different conditions and diseases,” including cancers, blood disorders, immune disorders, and autism. It adds that umbilical cord blood stem cells are “pure and plastic,” meaning that “they can become almost any tissue type in the body and may even be used to regrow entire organs.”

The researchers share the full results March 16 in the journal Cell; preliminary details on the case study were presented in February 2022 at the 29th annual Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections.

“The HIV epidemic is racially diverse, and it’s exceedingly rare for persons of color or diverse race to find a sufficiently matched, unrelated adult donor,” says Yvonne Bryson of UCLA, who co-led the study with fellow pediatrician and infectious disease expert Deborah Persaud of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. “Using cord blood cells broadens the opportunities for people of diverse ancestry who are living with HIV and require a transplant for other diseases to attain cures.”

Nearly 38 million people around the world live with HIV, and antiviral treatments, while effective, must be taken for life. The “Berlin patient” was the first person to be cured of HIV in 2009, and since then, two other men—the “London patient” and “Düsseldorf patient”—have also been rid of the virus.

All three received stem cell transplants as part of their cancer treatments, and in all cases, the donor cells came from compatible or “matched” adults carrying two copies of the CCR5-delta32 mutation, a natural mutation that confers resistance to HIV by preventing the virus from entering and infecting cells.

Only around 1% of white people are homozygous for the CCR5-delta32 mutation and it is even rarer in other populations. This rarity limits the potential to transplant stem cells carrying the beneficial mutation into patients of color because stem cell transplants usually require a strong match between donor and recipient.

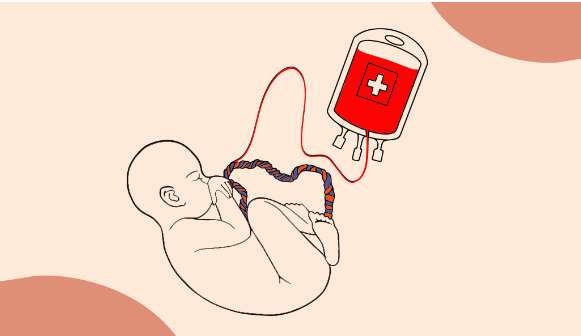

Knowing it would be almost impossible to find the New York patient a compatible adult donor with the mutation, the team instead transplanted CCR5-delta32/32-carrying stem cells from banked umbilical cord blood to try to cure both her cancer and HIV simultaneously. The patient received her transplant in 2017 at Weill Cornell Medicine thanks to a team of transplant specialists led by Drs. Jingmei Hsu and Koen van Besien. Her case was part of the NIH-sponsored International Maternal Adolescent AIDS Clinical Trials (IMPAACT) Network and was co-endorsed by the Adult AIDS Clinical Trials Network (ACTG).

The umbilical cord blood cells were infused alongside stem cells from one of the patient’s relatives to increase the procedure’s chance of success. “With cord blood, you may not have as many cells, and it takes a little longer for them to populate the body after they’re infused,” says Bryson. “Using a mixture of stem cells from a matched relative of the patient and cells from cord blood gives the cord blood cells a kick start.”

The transplant successfully put both the patient’s HIV and leukemia into remission, and this remission has now lasted more than four years. Thirty-seven months after the transplant, the patient was able to cease taking HIV antiviral medication. The doctors, who continue to monitor her, say she has now been HIV negative for more than 30 months since stopping antiviral treatment (at the time that the study was written, it had only been 18 months).

That question, sent to me by a colleague who is both a registered nurse and an expectant mother, stopped me in my tracks. As an OB-GYN physician, I naturally focus on the science of health care. Her email reminded me of the uncertainty expectant mothers now face as health risks and the health care system around them change amid this coronavirus pandemic.

While knowledge about the new coronavirus disease, COVID-19, is rapidly evolving and there are still many unknowns, medical groups and studies are starting to provide advice and answers to questions many expecting families are asking.

Do pregnant women face greater risk from COVID-19?

So far, the data on COVID-19 does not suggest pregnant women are at higher risk of getting the virus, according to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. However, as we have seen from the flu they are at greater risk of harm if they get respiratory infections. Pregnancy causes a variety of changes in the body and results in a slight immunocompromised state which can lead to infections causing more injury and damage.

Studies have not yet been done to show if having COVID-19 during pregnancy increases the chance of miscarriage, but there is some evidence from other illnesses. During the SARS coronavirus epidemic in 2002-2003, women with the virus were found to have a slightly higher risk of miscarriage, but only those who were severely ill.

Having respiratory viral infections during pregnancy, such as the flu, has been associated with problems like low birth weight and preterm birth. Additionally, having a high fever early in pregnancy may increase the risk of certain birth defects, although the overall occurrence of those defects is still low.